In my last posts I shared my recent article and talk I have on the earliest reference to 'A Study in Scarlet' by Conan Doyle.

That quote came from one of four letters held by the State Library of New South Wales, and I'm now posting each of the four letters with a transcription and some comments.

This third letter is RB/MSS004/1. This letter can be dated most precisely, as there are multiple references to stories being written published, and a reference to ACD's brother Innes' birthday.1 Bush Villas

Southsea

Dear Kate

Many thanks for your kind letter, as also for Rudder Grange which is capital - as far as I have read. It is the freshest, most original thing that I have got hold of for a long time. I was eating my breakfast this morning when I read that part where Pomona is shot out through the port hole by the two men, under the impression that she is a burglar - and I choked over it, then my breakfast and I got mixed up in a dreadful manner and a plug of toast got wedged into my windpipe, and I perspired tea and tears to such an extent that I have not been able yet to regain my usual moral serenity - 'for all of which, Jew, I hold thee answerable."

Has Dan donned the kilt yet, and is he to be one of the 15000 warriors whom we expect at Easter, for if he is not there officially he had better in any case come down as a man of peace, and we shall hold high wassail. I have been in a state of fearful indigence for some time but there are symptoms that a good time is coming - in which case I shall kick up my little legs a bit.

Today is Innes' birthday, and some fiend of a friend has presented him with a sword and several other lethal weapons - with which he lays in wait for me in unexpected corners and demonstrates how the Arab of the Desert attacks the unsuspecting caravan, by suddenly fetching me a clip over the head, or butting me in the stomach with a lance, which Mrs. Smith usually uses as a broom handle.

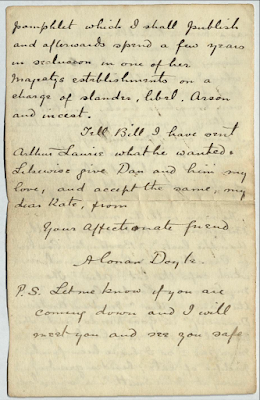

You seem to have been having high jinks. I don't know when I was tight last - I have been disgustingly respectable for a very long time back. You tell me nothing of your Temple Bar venture. I have one "Our Midnight Visitor" in T.B. next month - a queer sort of clotted-blood kind of story which would have pleased Pomona. Likewise I have "The man with the mattock" in Belgravia - a trifle more ghastly than the last. "Barrington Cowles" in Cassell's Saturday Journal which caps the lot. Also "The mysteries of a London Growler" in the same - Also "Modern Arctic Discovery" in Good Words, and "The Channel Tunnel" in a Cambridge Magazine - so I have been fairly prolific of late, besides grinding away at "John Smith" - a scurrilous pamphlet which I shall publish and afterwards spend a few years in seclusion in one of her Majesty's establishments on a charge of slander, libel, Arson and incest.

Tell Bill I have sent Arthur Laurie what he wanted. Likewise give Dan and him my love, and accept the same, my dear Kate, from

Your affectionate friend

A Conan Doyle

P.S. Let me know if you are coming down and I will meet you and see you safe.

-----------

And so to some general comments. I'm creating a set of annotations for each letter. Separately I have been tracing the life of Kate Bryson and the provenance of the letters, so let's set that aside for this letter.

This letter was written on a 31 March, and addressed from Bush Villas.

While the letter is undated, details in the letter allow very specific dating! Innes birthday was 31 March (1873) so the day/month is clear.

As to the year, it is complex. Innes arrived at Southsea to live with ACD in July 1882, and left three years later in the middle of 1885, just prior to ACD's marriage. As such the years when Innes celebrated his birthday as a resident of Southsea were 1883, 1884, and 1885.

Doyle describes with some braggadocio a number of stories and articles he expects to be published that could help with dating. In some cases, Doyle may have been overly optimistic about where stories would be published.

ACD refers to his short story "Our Midnight Visitor" as being published "in T.B. next month". That story was published in Temple Bar in February 1891 - so one conclusion that can be drawn is that it was published with some delay compared with Doyle's original expectations.

"The man with the mattock, in Belgravia" was eventually published anonymously under the title 'A Pastoral Horror' in The People on 21 Dec 1890.

Next is 'John Barrington Cowles', which was published in Cassell's in April 1884. In February 1884, ACD speculated to his mother that he may send the story to Cornhill.

"The mysteries of a London Growler" appeared as The Cabman's Story (sub-titled The Mysteries of a London "Growler") appeared in Cassell's on 17 May 1884

"Modern Arctic Discovery in Good Words" does not appear to have been published under this title, but may refer to The Glamour of the Arctic which appeared in July 1892.

"The Channel Tunnel in a Cambridge Magazine" is intriguing. Doyle published a letter in 1913 in the Times Magazine on the long-discussed concept of a tunnel between England and mainland Europe. The mention here suggests that Doyle had been meddling with the concept for some time.

And lastly Doyle points out these accomplishments "besides grinding away at "John Smith" - a scurrilous pamphlet". The story 'The Narrative on John Smith' was famously lost in the mail, re-written over a number of years from memory, then abandoned. Contemporary evidence including letters contained in 'A Life in Letters' that it was being written in 1883, and lost by February 1884 when Doyle informs his mother he will have to 'rewrite him from memory'.

In April 1884, ACD wrote to his mother and listed a similar set of stories as underway:

Where does this leave us? Based on all this evidence, it seems most likely that the letter was written on 31 March 1884.

---------

One other point reinforces 1884 as the year this letter was written. 'Has Dan decided to Don the kilt and is he to be one of the 15000 warriors....'. ACD is referring to a grand review of military Volunteers (reservists) on Portsdown Hill on Easter Monday April 14 (1884). Over 15,000 soldiers took part in this event, with estimates of up to 100,000 spectators! Doyle's question implies that Dan Bryson was a Volunteer. Geoffery Stavert (A Study in Southsea) points out that Doyle attended with a group of friends (did it include the Brysons?), and he wrote up the experience as 'Easter Monday with a Camera' in the British Journal of Photography.

'Rudder Grange' written by American author Frank R. Stockton was published in 1879, with a revised version published in 1885. It was a humorous novel set around a newly married couple who choose to live on a canal boat on a river in New Jersey. This domestic scenario is ripe for comedy, and leads to a range of misadventures for Euphemia and her husband, including a boarder named Pomona (an aspiring author, who at one point is launched through a porthole of the home/boat as a result of a case of mis).

'Bill' is William K Burton, Edinburgh friend who had relocated to London, and a fellow photography hobbyist.

'Mrs. Smith' was ACD's housekeeper in Southsea.

If only we knew what 'Arthur Laurie' wanted! Prof Arthur Pillans Laurie was a Scottish chemist and spectroscopist, who became an expert on studying paints, pigments, and dating paintings. At the time of this letter was written (1884) was based at King’s College, Cambridge where he was completing advanced studies. An interesting chemistry connection for ACD at a time when he was starting to think of creating a detective!

Edit/update: Many thanks to Edith Pounden for providing suggestions that have improved these transcriptions.